Helen Moore

‘There’s nothing new to write about nature,’ an older white male poet insisted almost twenty years ago. ‘It’s all been said before.’

I was sitting around a large table at his weekly “poetry surgery” in a back room of The Slug and Lettuce in Bath. I was one of a group of around ten aspiring poets, amongst whom I was probably the youngest, who met to share work and benefit from both his and each other’s feedback. I swallowed, unable to think of an adequate response. For a moment, his words seemed to hang in the air. No one spoke. Not a single voice questioned his astonishing assertion. That there was nothing new to write about Nature.

In policing the threshold of poetry, this gatekeeper never quite spelt it out, but I imagine he judged my work to be anachronistic, harking back to the Romantic tradition. In my gut I felt he was wrong. But it was 2004, perhaps 2005, and I had yet to identify as an ecopoet, to find my tribe. Nevertheless, I was reading a wide range of contemporary poetry, often in translation, as well as non-fiction, and making daily forays out around the fields and woods near where I lived in a small hamlet outside the former mining town of Radstock. Finding words to begin to describe perceptions and experiences, which later became the material for my debut ecopoetry collection, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins.

Fortunately, my relationship with my father had accustomed me to questioning male authority figures, and I carried on my own sweet way. Nevertheless, I have continued to wrestle with various forms of censure. A British poetry publisher was willing to bring out my second ecopoetry collection, provided I excise a quarter of the poems from the manuscript because they were ‘too political’. I have wondered whether he would have asked the same of a male poet. Was my work insufficiently “interior”/domesticated to fit his stereotypes of what a female poet should be writing? Disappointed, I turned instead to Permanent Publications, whose list is largely permaculture and ecology books. They helped me birth ECOZOA in 2015, and it was acclaimed as ‘a milestone in the journey of ecopoetics’ by the Australian poet, John Kinsella (qtd. in Moore, ECOZOA i). My work often does seem to resonate more overseas. The Italians regularly interview me and translate my poems, and their interest buoys my spirits. Shelley’s image of the poet as ‘a nightingale, who sits in darkness and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds’ is a state I know (680).

Darkness: materialism. Darkness: fear, entitlement, greed. Darkness: misogyny. Darkness: racism, and the reports denying it. Darkness: climate crisis. Darkness: Chernobyl, Fukushima. Darkness: state-sanctioned oppression. Darkness: slavery. Darkness: super quarries, tar sands, fracking. Darkness: industrial farming. Darkness: military-industrial complex. Darkness: pollution of rivers, estuaries, oceans. Darkness: wholesale logging of forests. Darkness: the killing of indigenous peoples trying to protect them. Darkness: genocide. Darkness: ecocide. Darkness: Anthropocene, Sixth Mass Extinction. Darkness: human unconsciousness. Darkness: generations of unhealed trauma. Darkness: our self-harming of our shared body, Earth.

In reading ‘A Defence of Poetry’, I hear Shelley’s bewitching voice alluding to his experience of his own times, two hundred years ago: ‘The cultivation of poetry is never more to be desired than at periods when from an excess of the selfish and calculating principle, the accumulation of the materials of external life exceed the quantity of the power of assimilating them to the internal laws of human nature’ (696). His words agitate the atoms of my heart, make me want to dance with him.

He surely knew the restorative effect of crafting a poem. ‘Whatever strengthens and purifies the affections, enlarges the imagination, and adds a spirit to sense, is useful,’ says Shelley (694). Finding language, imagery, form for what feels unspeakable and yet must be expressed helps a poet to witness, digest, transmute it.

Shelley: ‘Poetry … transmutes all that it touches … its secret alchemy turns to potable gold the poisonous waters which flow from death through life’ (698).

My own creative practice has helped me to grieve losses (personal and planetary), to channel rage at the insanity of an economic system pursuing infinite growth on a finite planet, and to restore my own balance, wellness, resilience. What waves of satisfaction follow in the wake of discovering a poem’s final shape, words arranged like blossoms along a branch! This two-dimensional sculpture, which reflects something of the poem’s content on page or screen and is the minor triumph of a craftswoman deploying her well-honed skills. Through writing I can stare into the abyss and create form, beauty.

Shelley: ‘Poetry … makes immortal all that is best and most beautiful in the world’ (698).

Amidst the ocean of information in which we drift, my poems honour and reverberate events, processes and beings that may otherwise be drowned. The scaling of London’s Shard by six women Greenpeace activists to protest Shell’s drilling in the Arctic (‘#Iceclimblive’). The melting of the Arctic ice sheet (‘Ice, an Elegy’). Flooding in India (‘Monsoon June’). Species extinction (‘The Fallen’, an elegy for extinct wildflowers in the British Isles). And in ‘A Wake to the Kittiwakes during London Fashion Week’, the ocean warming affecting bird life through the shifting food chain:

Sprats are out this season

and Lerwick feels absolutely the new Cannes

now the North Sea’s turned Mediterranean.

(1-3)

This witnessing is part of the poet’s role. Many poets whom I admire express it powerfully. Carolyn Forché’s first-hand experiences of the horror of the military junta in El Salvador in the late 70s. Audre Lorde on the killing of a black child by white police. Paul Celan and Charles Reznikoff on the Nazi Holocaust. Pablo Neruda on the bloodshed of the Spanish Civil War. Patrick Kavanagh evoking the Irish Famine. Shelley on the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. Yet none of these poets have required prefixes to qualify their relationship with poetry. So why “ecopoetry”?

There are various approaches and definitions, but for me ecopoetry is primarily a statement of intention to expand my consciousness. A desire born of the awareness of my conditioning within a culture that for centuries now has encouraged an exceptionalist perspective (through thought, language, behaviour) which “others” wild beings and ecosystems. In ‘Nature Story’, the opening poem of my debut collection, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins, I point at the language that perpetuates this relationship:

‘Natural history – the lexical preserve of stretched skin, glass cases, curators in drab ties … It keeps neat accounts and classifications, but cannot imagine the latency of woodland, a fallen trunk rife with spores, the rhythms of Lichen.’ (9)

Through the supposedly linear progress of white Western “civilisation”, we believe ourselves to have somehow transcended base Nature, risen above peoples who live in close alignment and reverence, and instead to have become superior, rational humans. In this worldview, Nature has little intrinsic value or inherent right to exist, but is primarily a resource to manage, manipulate, plunder, a context for leisure and entertainment, and to decorate our lives.

Shelley: ‘Poets … measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature’ (701).

In acknowledging my conditioning and seeing how it limits my ability to relate not only with wild Nature, but also the wilder aspects of my “humanimal” self, I want to widen the lens through which I understand myself and all beings. This is my ecopoetic stance. It makes me value not just the so-called “charismatic megafauna” (Whales, Tigers, Elephants, Dolphins, Polar Bears, Lions) but also the small creatures, which are often despised (Slugs, Flies, Ants, Spiders, Snakes, Worms). In my writings I bestow them all with capital letters to raise them from the margins to which our industrialised culture has relegated them.

Very quaint, very Emily Dickinson, all those shouting nouns –

but how else to see sisters and brothers in margins and ghettos?

(Moore, ‘Marginal, i’)

Honouring wild creatures as siblings recalls the tradition of St. Francis of Assisi and aligns me with many indigenous peoples. And, it would appear, with our ancient ancestors who once inhabited this North Atlantic archipelago. The interlaced knotwork of Picts and Celts suggests an awareness of our sacred interconnection with the birds and animals their carvings represent.

‘Fifteen hundred years ago, in this Pictish kingdom of Fortriu – Brochheid its royal seat – a world where Goose & Salmon were revered, incised together in stone, then placed in a burial cist on land now known as Easterton of Roseisle.’ (Moore, ‘Findhorn Bay’)

Shelley: ‘Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration’ (701).

Finding myself inspired, I want to share my inspiration with others. Its sources are multiple and include the scientists and astronauts who reveal the miracle of Earth Life. Gaia, our animate planet, this self-regulating super-organism, which for millennia sustained our “Goldilocks” conditions – not too hot, not too cold – enabling the unfurling of our incredible biodiversity. And our Moon, at just the right distance from Earth, conducting the oceans’ ebb and flow, which gave marine life the chance to evolve on dry land. Fossils fascinate me, as do earth sciences, geography, anthropology, history, ecopsychology and ecophilosophy. I love to research, to dialogue with ecologists and green thinkers. To translate their ideas through my ecopoetry.

A direct communion with Nature also serves to resource me. Practising “wild writing” involves creating sacred time and space to tune out of the digital realm, slow myself, clear my mind, connect with my body, and open myself to what Life wants to show me. My practice is always co-creative – a dance with other beings.

Shelley: ‘A man … must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasures of his species must become his own’ (682).

Here I part company with Shelley to dance with poets who explore the experiences of species other than their own. This is classic ecopoetic territory, and it requires shapeshifting – a mode revealed in the poetry of the ancient Welsh bard, Taliesin – learning to extend the imagination in an act of empathy, walking a mile in another’s fur, feathers, scales, embodying something of their energy. This is not to anthropomorphise in cartoon mode. But to take on the serious concern of acknowledging that wild beings communicate in languages largely incomprehensible to us. That they cannot access our words to share their perceptions, speak of their suffering.

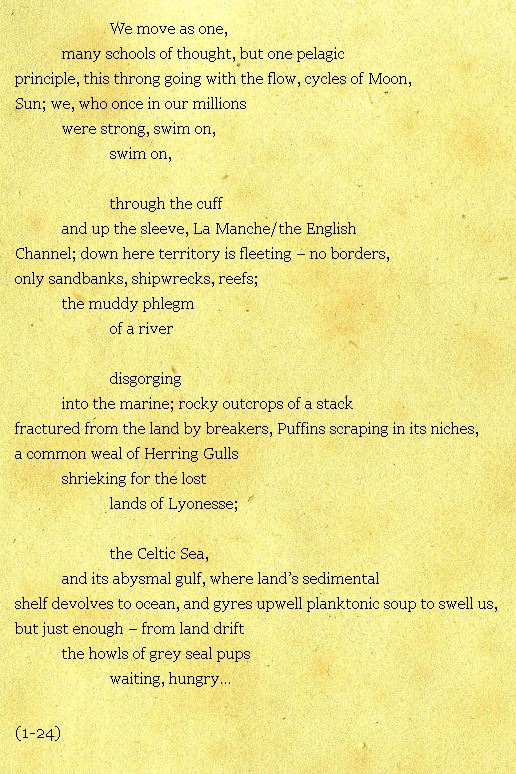

In Gary Snyder’s view, this tuning into ‘other voices than simply the social or human voice’ is about being ‘an early warning system that hears the trees and the air and the clouds and the watersheds beginning to groan and complain’ (71). And it is about advocating ‘for a realm for which few men will stand up’ (49). For Snyder, such poetry moves beyond self-expression into an expression of ‘all of our selves’ (65, original emphasis). In ‘The Unsung Pilchard’, my ecopoem remembering the once prolific Pilchard schools off the Cornish coastline, their voices sound in unison:

A school of Pilchard expressed in fish-shaped stanzas. In Redstart: An Ecological Poetics, John Kinsella and Forrest Gander touch on the myriad opportunities of form to represent Nature, acknowledging that writing is a constructed system, and thus: ‘A poem expressing a concern for ecology might be structured as compost, it might be developed rhizomatically, it might be described as a nest, a collectivity’ (13). Ecopoetry values organic forms, while the language that ecopoets choose to express ‘all our selves’ emerges primarily from the body, from what Bill Plotkin calls ‘Five Ways of Knowing’ – sensing, feeling, intuiting, imagining and thinking.

In arising from this embodiment, might such poetry have a greater chance of transmission, and even of occasioning transformation? Jorie Graham indicates this in her notion of poetry’s contagious quality: ‘Poems … want to go from body to body. Built in is the belief that such community – could one even say ceremony – might save the world’. But is she overstating things? How might the context through which poems travel create the kind of change we need?

I believe Graham’s insight touches at the root of our intersecting ecological and social crises. Twin problems of perception and imagination. In industrialised cultures we have lost the ability to perceive Life as sacred and to embody our relationship with it as such – to sing, honour, praise, restore Life through community and ceremony. Instead, we measure and classify it with the rational mind, seek every which way to exploit it. And whilst waking up to the fact that our industrialised cultures are causing great harm, we struggle to collectively imagine ways of living and being with Earth as our community.

Back to Shelley, who begins ‘A Defence of Poetry’ by describing ‘two classes of mental action’ – reason and imagination, the latter being poetry’s domain (674). Evidently imagination is central to a poet’s capacity to craft fresh imagery which ‘strips the veil of familiarity from the world, and lays bare the naked and sleeping beauty which is the spirit of its forms’ (698). Here Shelley alludes to the spiritual dimensions of Life, i.e., the formless, or Oneness, which underlies form. And is always here – accessible in the stillness of Now.

Yet the ecopoetic imagination extends also into visioning futures. How might the myriad solutions that eco-aware humans have been developing for decades in the Global North, along with the sustainable practices of traditional lifestyles in the Global South, and of indigenous cultures, inspire regenerative futures that are suited to the needs, resources and sensitivities of cultures and place? Clearly, we must imagine beyond nightmarish dystopias. Might a future London echo the scene I describe in ‘Climate Adaptation #2’?

‘The Sun presses down with many hands –

we are pig iron smelted in the furnace; Trafalgar

Square bakes like Tahrir Square without its people.

And we have slowly adapted – come out at night

when it’s cooler, stroll the canals fashioned

by the uprisings of the Thames. Little Venice

has spread; we’re the Venice of the North

now the original has gone. And there’s no choice

but to be in what’s left of Europe – Mother

Earth has moored humanity together at her table,

and she’s at the centre of all our decisions.

From our boat, I watch the river swimming

with the gibbous Moon; we use her light to sow

our seeds, and harvest every month when she dies.

We live by lunulations – have become silvery,

left-handed humans, who see their shadows …’

(1-16)

Shelley: ‘Poets are … the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present, the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire’ (701).

Ecopoetry dares to trumpet truth to power, to ‘show us the hands of our prime minister and his henchmen | in the pockets of BAE Systems, touting for business | with morbid regimes and crackpot dictators’ (Moore, ‘Kali’, 10-12). It is political in that it exposes where power lies, while longing for power to be shared in the co-creative, horizontal mode inherent within balanced, healthy ecosystems, where leadership is never entrenched. Does this make ecopoets Shelley’s ‘unacknowledged legislators’ (701)?

In holding Shelley’s spirit close, I sense him owning that the time for giving our power away to others is over. We must all become legislators now. We have no choice but to participate in cocreating a world for which our children’s children will thank us. A world where “ecopoetry” will simply be “poetry” again.

Works Cited

Gander, Forest, and Kinsella, John. Redstart: An Ecological Poetics. University of Iowa Press, 2012.

Graham, Jorie. ‘The Art of Poetry No. 85’. Interview with Thomas Gardner. The Paris Review,165 (2003). https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/263/the-artof-poetry-no-85-jorie-graham. Accessed 18.06.2021.

Moore, Helen. ‘A Wake to the Kittiwakes during London Fashion Week’, in Hedge Fund and Other Living Margins. Shearsman, 2012.

Moore, Helen. ‘Nature Story’, in Hedge Fund.

Moore, Helen. ‘Marginal, i’, in Hedge Fund.

Moore, Helen. ‘The Unsung Pilchard’, in Hedge Fund.

Moore, Helen. ‘Climate adaptation’, in ECOZOA. Permanent Publications, 2015.

Moore, Helen. ‘Kali Exorcism’, in ECOZOA.

Moore, Helen. ‘Findhorn Bay, Waves of Flow & Flight’. Soundcloud, n.d. https://soundcloud.com/user-561958272/sets/findhorn-bay-waves-of-flow. Accessed 18.06.2021.

Plotkin, Bill. Soulcraft. New World Library, 2003.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. ‘A Defence of Poetry’, in The Major Works. Ed. by Zachary Leader and Michael O’Neill. Oxford University Press, 2003. Pp. 674-701

Snyder, Gary. The Real Work: Interviews & Talks, 1964-1979. New Directions, 1980.

Helen Moore is a British ecopoet, socially engaged artist and writer. She has published three ecopoetry collections, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins (Shearsman Books, 2012), ECOZOA (Permanent Publications, 2015), acclaimed by John Kinsella as ‘a milestone in the journey of ecopoetics’, and The Mother Country (Awen Publications, 2019) exploring aspects of British colonial history. Helen offers an online mentoring programme, Wild Ways to Writing, and works with students internationally. In 2020 her work was nominated for the Forward and Pushcart Prizes and received grants from the Royal Literary Fund and Arts Council England. She’s currently collaborating with Cape Farewell in Dorset on RiverRun, a project working with scientists and farmers in Dorset to examine pollution in Poole Bay and its river-systems. www.helenmoorepoet.com